by Gina Pugliese (Vice President, Premier Safety Institute)

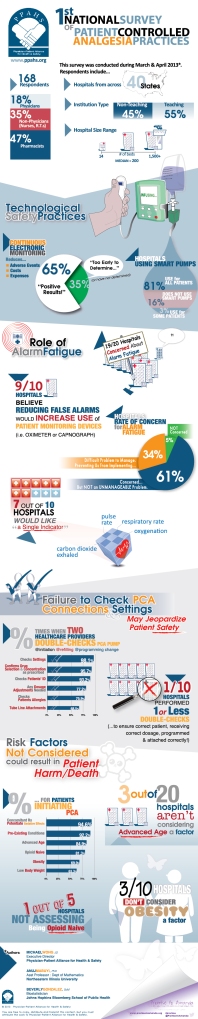

In my post yesterday, I discussed the dangers of alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is considered the leading health technology hazard, according to the ECRI Institute’s top 10 health technology hazards.

And with 19 out of 20 hospitals (surveyed by the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety) ranking alarm fatigue as a top patient safety concern, it’s become an issue we need to address. And fast.

As AAMI notes in its recent Safety Innovations series about alarm management at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, it often takes “major events to draw attention to alarm system shortfalls.”

The hospital recently experienced 2 major sentinel events – both of which involved delayed responses to cardiac monitors. After the hospital addressed the problem in a multidisciplinary fashion:

- Alarm signals dropped by a third

- Response times significantly shortened

- Staff competency about alarm management improved considerably

In another example, The Johns Hopkins Hospital used data to determine baseline alarm priority levels. They evaluated the effectiveness of their improvement efforts, which included changes in default parameters and daily electrode changes. The results? Up to 74% reduction of alarm conditions and signals hospital-wide.

Hospitals have until 2016 to establish an alarm management program. Between now and then, the Joint Commission advises they set upon the work of compiling best practices.

Here are the top 10 things you can do to reduce alarm fatigue

1. Inventory all alarm-equipped medical devices and identify proper default settings and limits.

2. Establish guidelines for alarm settings, and indicate when alarms are not “clinically necessary.”

3. Establish guidelines for safely customizing alarm settings for individual patients and restoring them to default when finished.

4. Set up an inspection, cleaning and maintenance program for alarm-equipped medical devices, and test them regularly.

5. Orient staff on your organization’s process for safe alarm management and responsibility for response.

6. Routinely change single-use sensors to avoid false or nuisance alarms.

7. Determine whether the acoustics in patient care areas allow alarms to be easily heard, and make adjustments where needed.

8. Set your priorities for replacing aging monitors with newer technology.

9. Establish a multidisciplinary team of clinicians and representatives from clinical engineering, information technology and risk management to address alarm safety and management.

10. Share information about alarm-related incidents, prevention strategies and lessons learned.

What does the future hold?

Imagine multiple bedside monitoring devices combining electronic information on a patient to provide a single notification or alarm. This was discussed at the AAMI summit on clinical alarms.

A call for stakeholder organizations to develop standards and language for data output and exchange that would make this a reality, and would help integrate data from different alarm systems and systems from different manufacturers.

Wouldn’t that be nice?

For now, we are still facing a patient safety problem. Desensitization to alarms is a serious concern, and must be dealt with promptly. If we improve alarm management, the problem of alarm fatigue should take care of itself.